About This Blog

Science Happenings with Rightler is a blog designed to share information about the cool stuff that is going on in the world of science. New discoveries, cosmic fluff, and all in between are grist for the mill. I will be giving my own take on the events as they happen.

Saturday, February 22, 2014

Friday, February 21, 2014

Ever wonder why we tag animals?

Part of why we radiocollar and tag animals is because a) we can find them and b) we can assess the health of the greater population of that study species.

Here's a great video from the CBC - Canadian Broadcasting Company - about tagging and checking the health of black bear populations.

Watch out for the cuteness!

Here's a great video from the CBC - Canadian Broadcasting Company - about tagging and checking the health of black bear populations.

Watch out for the cuteness!

Thursday, February 20, 2014

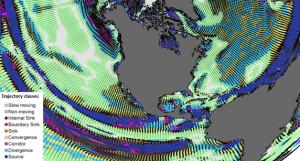

New Maps Show How Habitats My Shift with Climate Change

As regional temperatures shift with climate change, many plants and animals will need to relocate to make sure they stay in the range of temperatures they're used to.

For some species, this shift will mean a fairly direct adjustment toward higher latitudes to stay with cooler temperatures, but for many others, the path will take twists and turns due to differences in the rate at which temperatures change around the world, scientists say.

Now, a team of 21 international researchers has identified potential paths of these twists and turns by mapping out climate velocities— the speed and intensity with which climate change occurs in a given region — averaged from 50 years of satellite data from 1960 through 2009, and projected for the duration of the 21st century.

"We are taking physical data that we have had for a long time and representing them in a way that is more relevant to other disciplines, like ecology," said co-author Michael Burrows, a researcher at the Scottish Marine Institute. "This is a relatively simple approach to understanding how climate is going to influence ocean and land systems."

Where species come and go

The resulting maps indicate regions likely to experience an influx or exodus of new species, or behave as a corridor or, conversely, a barrier, to migration. Barriers, such as coastlines or mountain ranges, could cause local extinctionsif they prevent species from relocating, the team says. [Maps: Habitat Shifts Due to Climate Change]

"For example, because those environments are not adjacent to or directly connected to a warmer place, those species from warmer places won't be able to get there very easily," Burrows told Live Science. "They might still get there in other ways, like on the bottoms of ships, but they won't get there as easily."

Warming waters and changes in regional ocean currents have already caused the long-spined sea urchin, previously only found as far south as southern New South Wales in Australia, to migrate farther south along the eastern Tasmanian coast, co-author Elvira Poloczanska, of Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, said in a statement. The urchins have decimated kelp forestsin the region, demonstrating the domino effect that temperature changes can have in regional ecosystems.

The researchers hope the maps will help conservation biologists predict where certain species will migrate in the future, and help management organizations devise conservation plans accordingly.

The maps' accuracy has some limitations, though. For example, the study only assesses changes in temperature, and excludes other factors that determine habitat ranges, such as precipitation and species interactions. The maps also have a limited spatial resolution of only 1 degree latitude by 1 degree longitude, which may not distinguish between certain types of environments like the tops of mountains and neighboring areas, Burrows said.

Deceiving appearances

Tony Barnosky, a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley who studies global ecological change but was not involved in this study, recognizes these limitations, but he still thinks the maps provide a helpful step forward.

"Temperature is a good place to start, because it is fairly straightforward to get those measurements, and we know that many species have this very rough correlation with temperature boundaries," Barnosky told Live Science. "It would also be useful to have these kinds of studies for things like precipitation and number of hot days in a year, but that is a scale of data and resolution that is much harder to get, so I think this sort of study is a good way to enter into the problem."

The study is also helpful for identifying regions that might not appear to be undergoing change but that are susceptible to passing thresholds of rapid change sooner than other regions, Barnosky said. Some mountainous regions, such as the Andes and the Himalayas, for example, appear to be experiencing slower rates of change than flat-lying, inland regions like the Australian Outback, according to the report.

The study findings were detailed Feb. 10 in the journal Nature.

Thursday, February 6, 2014

Wobbly Alien Planet with Wild Seasons Found by NASA Telescope

.

View gallery

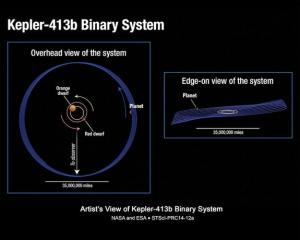

This illustration shows the unusual orbit of newly discovered planet Kepler-413b.

Astronomers have discovered an alien planet that wobbles at such a dizzying rate that its seasons must fluctuate wildly.

Throughout all of the planet's fast-changing seasons, however, no forecast would be friendly to humans. The warm planet is a gassy super-Neptune that orbits too close to its two parent stars to be in its system's "habitable zone," the region where temperatures would allow liquid water, and perhaps life as we know it, to exist.

The faraway world, which lies 2,300 light-years away in the constellation Cygnus, was discovered by NASA's planet-hunting Kepler space telescope. Dubbed Kepler-413b, the planet orbits a pair of orange and red dwarf stars every 66 days.

Kepler was designed to detect exoplanets by noticing the dips in brightness caused when these worlds transit, or cross in front of, their parent stars. Normally these transits occur in a regular pattern, but Kepler-413b behaved strangely.

"What we see in the Kepler data over 1,500 days is three transits in the first 180 days (one transit every 66 days), then we had 800 days with no transits at all," study lead investigator Veselin Kostov, of the Space Telescope Science Institute and Johns Hopkins University, said in a statement. "After that, we saw five more transits in a row."

Kostov and colleagues concluded that the planet's wobble must be causing it to move up or down relative to our view, so much so that it sometimes doesn't appear to cross in front of its parent stars. (A NASA statement compared the planet's motions to a child's spinning top on the rim of a wobbling bicycle wheel rotating on its side.)

The scientists determined that the planet's axial tilt can vary by as much as 30 degrees over 11 years,. For comparison, Earth's tilt has shifted 23.5 degrees over 26,000 years. The researchers say it's amazing that this planet is wobbling, or precessesing, so much on a human time scale, and they say it's possible that there are other planets like Kepler-413b awaiting discovery.

"Presumably there are planets out there like this one that we're not seeing because we're in the unfavorable period," Peter McCullough, a team member from STScI and JHU, said in a statement.

Kostov and colleagues are still investigating what causes the extreme wobble of the gas planet, which has a mass about 65 times that of Earth. They say Kepler-413b's orbit may have been tilted by other planets in the system or by a nearby star exerting gravitational influence.

The research was detailed in the Jan. 29 issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

Kepler was disabled last year after suffering a major failure, but engineers are have developed a possible new mission that would use the spacecraft in its compromised state. The $600 million Kepler mission launched in 2009 and has detected more than 3,500 exoplanet candidates to date.

Disappearance of wildflowers may have doomed Ice Age giants

A Mammoth tusk extracted from ice complex deposits along the Logata River in Taimyr, Russia, is

shown in this undated handout photo provided by Professor Per Moller February 5, 2014.

Flower power may have meant the difference between life and death for some of the extinct giants

of the Ice Age including the mighty woolly mammoth and woolly rhinoceros.

shown in this undated handout photo provided by Professor Per Moller February 5, 2014.

Flower power may have meant the difference between life and death for some of the extinct giants

of the Ice Age including the mighty woolly mammoth and woolly rhinoceros.

By Will Dunham

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Flower power may have meant the difference between life a

nd death for some of the extinct giants of the Ice Age, including the mighty woolly mammoth and woolly rhinoceros.

Scientists who studied DNA preserved in Arctic permafrost sediments and in the remains of such ancient animals have concluded that these Ice Age beasts relied heavily on the protein-rich wildflowers that once blanketed the region.

But dramatic Ice Age climate change caused a huge decline in these plants, leaving the Arctic covered instead in grasses and shrubs that lacked the same nutritional value and could not sustain the big herbivorous mammals, the scientists reported in the journal Nature on Wednesday.

The change in vegetation began roughly 25,000 years ago and ended about 10,000 years ago - a time when many of the big animals slipped into extinction, the researchers said.

Scientists for years have been trying to figure out what caused this mass extinction, when two-thirds of all the large-bodied mammals in the Northern Hemisphere died out.

"Now we have, from my perspective at least, a very credible explanation," Eske Willerslev of the University of Copenhagen, an expert in ancient DNA who led an international team of researchers, said in a telephone interview.

The findings contradicted the notion that humans arriving in these regions during the Ice Age caused the mass extinction by hunting the big animals into oblivion - the so-called overkill or Blitzkrieg hypothesis.

"We think that the major driver (of the mass extinction) is not the humans," Willerslev said, although he did not rule out that human hunters may have delivered the coup de grace to some species already diminished by the dwindling food supplies.

The Arctic region once teemed with herds of big animals, in some ways resembling an African savanna. Large plant eaters included woolly mammoths, woolly rhinos, horses, bison, reindeer and camels, with predators including hyenas, saber-toothed cats, lions and huge short-faced bears.

The scientists carried out a 50,000-year history of the vegetation across the Arctic in Siberia and North America.

They obtained 242 permafrost sediment samples from various Arctic sites and studied the feces and stomach contents from the mummified remains of Ice Age animals recovered in places like Siberia. They determined the age of the samples and analyzed the

DNA.

While many scientists had thought the ecosystem had been grasslands and the big animals were grass eaters, this study showed it instead was dominated by a kind of plant known as forbs - essentially wildflowers.

"The whole Arctic ecosystem looked extremely different from today. You can imagine these enormous steppes with no trees, no shrubs, but dominated by these small flowering plants," Willerslev said.

Christian Brochmann, a botanist at the Natural History Museum at the University of Oslo, said the permafrost contained "a vast, frozen DNA archive left as footprints from past ecosystems," that could be deciphered by exploring animal and plant collections already stored in museums.

Bear Bile-Extracting Farms Near Collapse in South Korea

.

View photo

In this photo taken on Jan. 24, 2014, a bear stretches its forepaw through a cage at a bear farm in Dangjin, south of Seoul, South Korea. Several bears lie stacked on top of each other, as still as teddy bears, as they gaze out past rusty iron bars. Others pace restlessly. The ground below their metal cages is littered with feces, Krispy Kreme doughnuts, dog food and fruit. They’ve been kept in these dirty pens since birth, bred for a single purpose: to be killed for their bile. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

DANGJIN, South Korea (AP) -- Several bears lie on top of each other, as still as teddy bears, as they gaze out past rusty iron bars. Others pace restlessly. The ground below their metal cages is littered with feces, Krispy Kreme doughnuts, dog food and fruit. They've been kept in these dirty pens since birth, bred for a single purpose: to be killed for their bile.

But these bears aren't dying. The industry is.

Though their bile has been used as medicine in Asia for thousands of years, cheaper foreign sources, growing skepticism over bear bile's medicinal value and worries about international condemnation have led to a huge drop in South Korean demand. Kim KwangSoo, the owner of this farm in Dangjin, about 120 kilometers (about 75 miles) south of Seoul, said he hasn't had a bear bile customer in five years.

That, however, doesn't ensure the animals a peaceful future. The government is offering farmers money and incentives to sterilize or slaughter their bears, but the farmers are demanding much more.

Kim, secretary general of a bear farmers' association, said farmers are considering suing or even more drastic measures — such as harming their bears — if they can't reach a deal. He said farmers raised the issue of greater government compensation Thursday during a meeting with government officials and civilian experts, and that they will meet again this month.

To highlight their grievances, farmers in November brought caged bears to downtown Seoul and near a government complex in the city of Sejong. Kim said farmers are now considering hauling bears, 20 per cage, to the Sejong government complex in the hope that the fighting, cramped animals will bring them attention.

"People talk about animal welfare ... but bear farmers aren't getting any welfare," said Yun Youngdeok, who runs a bear farm near Seoul. "We feel like we are dying earlier (than our bears)."

South Korea is one of the few countries that allow the farming of bears to extract bile for traditional medicine. About 50 farms are raising about 1,000 bears, mostly Asiatic black bears, also known as moon bears. They are the descendants of bears imported from Malaysia and other Southeast Asian countries when bear farming began here in the early 1980s.

Kim said South Koreans were once willing to pay between 20 million to 30 million won ($18,450-$27,680) to have a bear slaughtered for its bile. But farmers ran into trouble about a decade ago, when bear bile from China and Vietnam became more readily available.

Now the farmers have an even bigger problem: Bear bile just isn't popular. South Korea imported only 2.8 kilograms (6.2 pounds) of dried forms of bear gall bladders between 2008 and 2012, according to the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. In 2011, about 94 percent of South Koreans surveyed by the private Hangil Research Center said they had never bought bear bile and had no intention of doing so. The telephone survey of 1,000 people had a margin of sampling error of plus or minus 3.1 percentage points.

The bear farmers' association says most of its members haven't sold any bile in five or six years. Meanwhile, huge debts from feeding and maintaining the bears are mounting. Kim, who has about 270 bears at his farm, said their upkeep costs him about 300 million won ($276,750) annually.

The Environment Ministry said it plans to spend about 6.2 billion won ($5.7 million) by 2016 on an anti-breeding campaign, but that no final compensation plan for farmers has been settled. Officials wouldn't elaborate but called the campaign a meaningful first step toward ending the industry.

Kim, however, said ministry officials recently proposed that farmers receive about 1.3 million won ($1,200) from the government for the sterilization of one bear; 400,000 won ($370) annually for feed cost; and 1.5 million won ($1,390) for the slaughter of bears older than 10.

Farmers say that isn't enough, and that the government should take more responsibility for their troubled businesses because officials earlier encouraged them to raise bears. The government started allowing bear imports in 1981, but Environment Ministry officials say there are no official documents showing it encouraged bear farming.

Bear bile has been used in many Asian countries to treat a range of illnesses, including abscesses, hemorrhoids, epilepsy and cysts. Until recently, many South Koreans believed bear bile could cure all diseases and bolster vitality and stamina.

"It's not a panacea," said Kim Hocheol, a Korean traditional medicine professor at Seoul's Kyung Hee University. He said there are also alternative medical ingredients that can replace bear bile, so most traditional doctors in South Korea don't suggest expensive bear parts.

In China, where bear bile harvesting is legal, more than 10,000 bears are kept in farms, their cages sometimes so small that they are unable to turn around or stand on all fours, according to Animals Asia, a Hong Kong-based animal welfare group. The organization said that about 2,400 bears are illegally raised in farms in Vietnam, which outlawed the practice in 2005.

As for the South Korean bears, their lives may improve little beyond their current state no matter how much government money farmers get. South Korea is trying to restore a sub-species of the moon bear, but farm bears don't count because they are likely mixed breeds.

So they probably will stay in places like the Dangin farm, the largest of its kind in South Korea, as long as they live.

The cages, set up just above the ground, are in varying sizes. Ten 100-kilogram (220-pound) bears share a 40-square-meter (430-square-foot) enclosure, and four 130-kilogram (290-pound) bears share 16 square meters (170 square feet).

Some bears are missing a paw, or an ear. Kim, the owner, said they were attacked by bigger bears when they were cubs. Some bears are caged by themselves because they are too violent.

Some bears spend their days repeatedly moving back and forth. It's a motion researchers say is triggered from the stress of being locked up in a small place.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)